What transpired in the Asia Cup Super Over

The final Super 4s match of the Asia Cup on September 26 turned into a nail‑biter when India and Sri Lanka both posted 202 for 5. With scores level, the contest moved to a Super Over to decide the winner. India’s opening over was steady, but the real drama unfolded on Sri Lanka’s fourth ball.

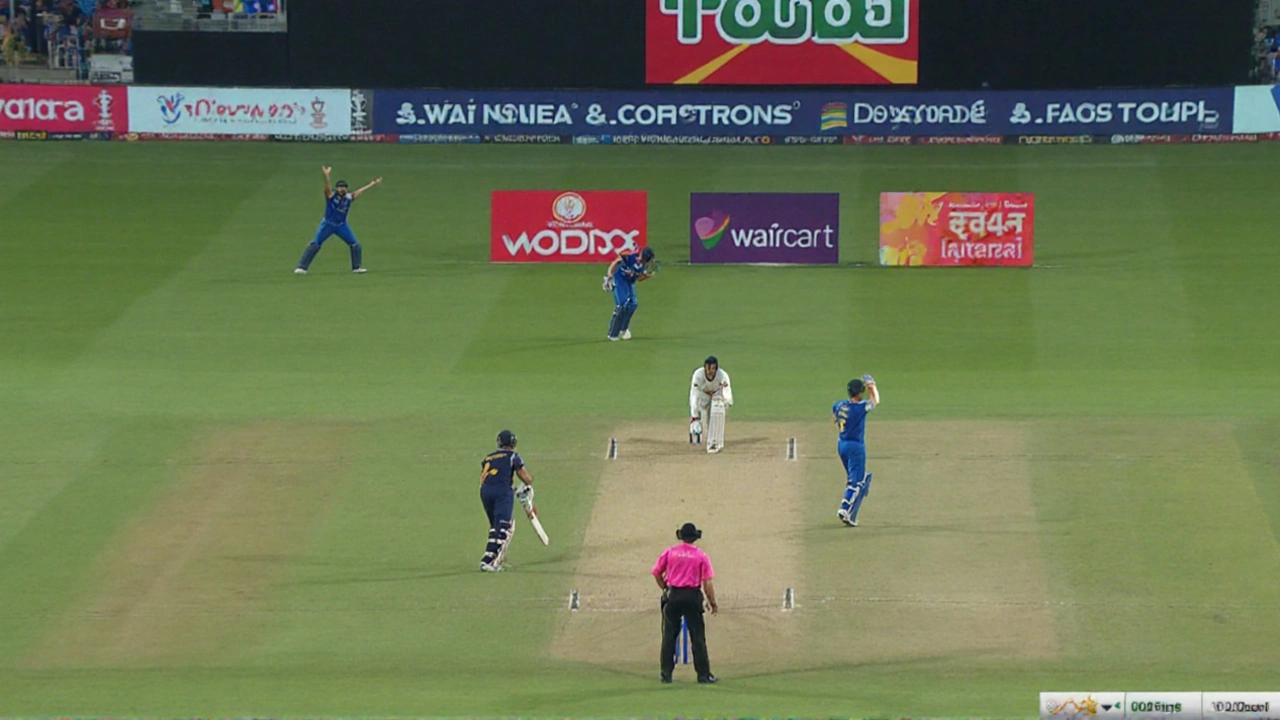

Dasun Shanaka, Sri Lanka’s captain, edged his bat and missed the delivery. The ball flew straight to Indian wicket‑keeper Sanju Samson, who collected it cleanly and appealed for a catch. Umpire Gazi Sohail lifted his finger, signaling out caught behind. At the same moment, Shanaka, startled by the catch, stepped out of his crease and was sprinting for the non‑striker’s end, appearing ready for a run‑out.

Spectators assumed two dismissals would be recorded – caught behind first, then run‑out. Instead, Shanaka lodged a DRS challenge on the catch. Video evidence showed no edge, and the decision was overturned, granting him not out for the caught‑behind appeal.

Why the dead‑ball rule kept him safe

Even though the catch was cancelled, the run‑out did not happen. The answer lies in MCC’s Rule 20.1.1.3, which states that the ball becomes dead the instant a batter is dismissed. Because the umpire had already called Shanaka out caught behind, the ball was considered dead from that exact moment, freezing play before any run‑out could be effected.

When the DRS reversed the first decision, the status of the ball did not retroactively change; it remained dead from the instant the umpire first marked a dismissal. Consequently, any subsequent actions – including the run‑out attempt – fell outside the scope of the play and could not result in a further dismissal.

To illustrate the sequence, here is a quick rundown:

- Ball delivered – Shanaka misses, ball to Samson.

- Samson catches, appeals caught behind.

- Umpire signals out – ball deemed dead.

- Shanaka, out of his crease, appears to be run‑out.

- DRS review shows no edge – catch overturned.

- Because the ball was already dead, the run‑out is invalid.

The incident threw light on how tightly cricket’s law book ties timing to outcomes. Fans and pundits erupted on social media, questioning why a player could stroll out of his ground without penalty. The rulebook, however, gave a crystal‑clear answer: once an umpire declares a dismissal, the ball ceases to be in play, and any later events are null.

Beyond the controversy, the match itself was a showcase of firepower. India’s Abhishek Sharma smashed 61 off 31 balls, while Tilak Varma and Sanju Samson added 49* and 39 respectively, posting the tournament’s highest total. Sri Lanka responded with Pathum Nissanka’s maiden Asia Cup century (107) and Kusal Perera’s tidy 58, mirroring the Indian score exactly.This episode underscores the importance of knowing obscure regulations, especially in high‑stakes formats like the Super Over. While technology can overturn a mistaken edge, it cannot rewrite the moment the ball was deemed dead, leaving players and fans to grapple with the fine print of the game.